Englsh4Today Privacy Policy

Englsh4Today Privacy Policy

In this Privacy Policy, “we”, “us” and “our” refers to: English4Today.com.

This is privacy policy sets out how English4Today uses and protects any information that you provide, whilst using English4Today’s products and services . English4Today may change this policy as and when necessary. In the case of changes to this policy, we will provide a more prominent notice (including email notification of privacy policy changes).

1. What information we collect about you and how we use this information

1.1 Account and Profile Information

You don’t have to create an account to use the non-member sections of this website, such as searching and viewing public information areas, forums, topics and posts. If you do choose to create an account, you must provide us with some personal data so that we can provide our services to you. This includes a display name (for example, “John Doe”), nickname (for example, @john-doe) a username (for example, johnxdoe), a password, and an email address. Your display name and nickname is always public, but you can use either your real name or a pseudonym. After the registration your account display name, nickname and username are the same. We recommend to change display name and nickname to keep the username private and secure. You can change those in your account editing page.Once you have registered and created an account, you have the option of adding to your profile information and adjusting your privacy settings:

- Member Title

- Avatar

- Biography (About Me)

- First name and Family name

- Teacher or Student status

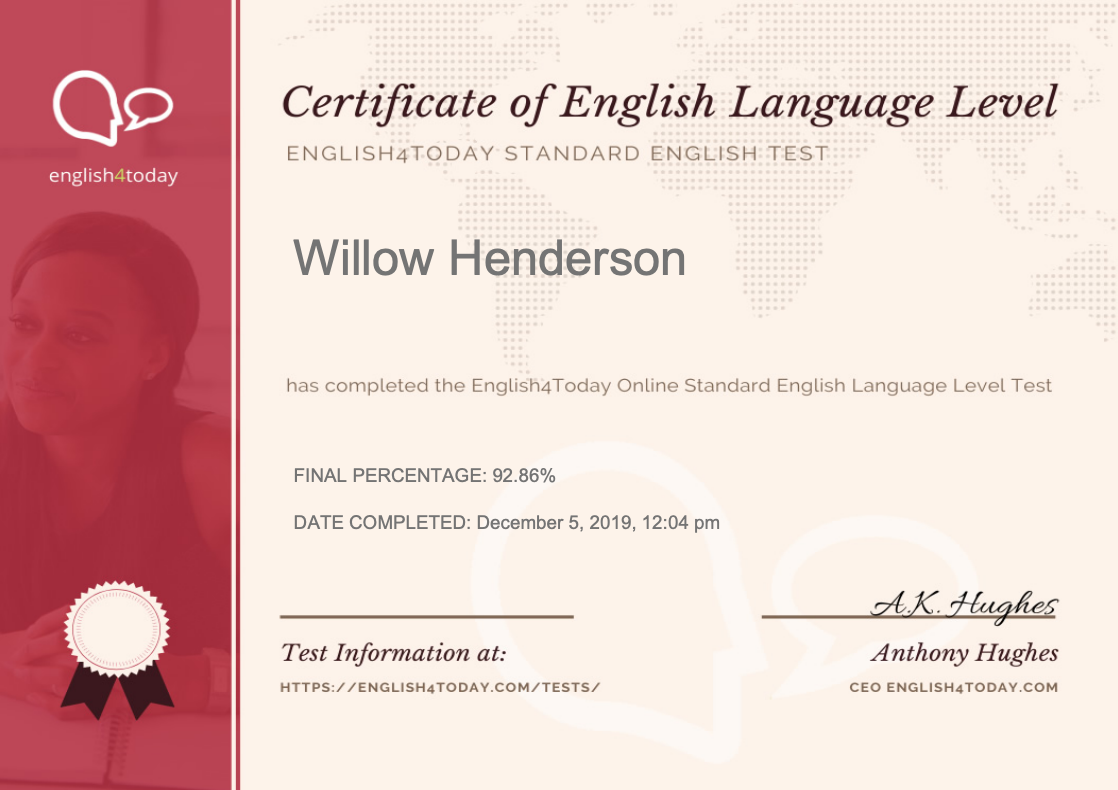

- Your English language level

- Social Network Account addresses

- Location (Country / City or Town)

- Timezone

- And other details you have the option to add to your profile information to be displayed to our community.

Additionally, whilst using English4Today the following information may be collected (not public):

- Internet Protocol (IP) address (not public)

- Geographical location

- Browser type and version (not public)

- Operating system (not public)

- Referral source (not public)

- Length of visit, page views, website navigation and any other related browsing activity

Most activity on English4Today is public, including your profile information mentioned above. You also may choose to publish your location in your profile. Information posted about you by other people who use our forum may also be public. For example, other people may mention you using @nickname in posts.You are responsible for your topics, posts and other information you provide through our services, and you should think carefully about what you make public, especially if it is sensitive information.You may choose to register connecting your account to accounts on another service (e.g. Facebook login), and that other service may send us information about your account on that service. We use the information we receive to provide you features like cross-posting or cross-service authentication, and to operate our community. We create new account in our community for you based on your third party account information you share.

1.2 Contact Information

We use your contact information, such as your email address, to authenticate your account and keep it – and our services – secure, and to help prevent spam, fraud, and abuse. We also use contact information to personalise our services, enable certain account features for example, for login verification, reset password, to send you information about our community and notify on new replies to your subscribed forums and topics. You can also unsubscribe from any email notifications.If you email us, we will keep the content of your message, your email address, and your contact information to respond to your request.

1.3 Private Messages and Non-Public Communications

We provide certain features that let you communicate more privately or control who sees your content. We share the content of your Private Messages with the people you’ve sent them to; we do not use them to serve you ads. When you use features like Private Messages to communicate, remember that recipients have their own copy of your communications on English4Today – even if you delete your copy of those messages from your account – which they may duplicate, store, or re-share.

1.4 Cookies

A cookie is a small piece of data that is stored on your computer or mobile device. Like many websites, we use cookies and similar technologies to collect additional website usage data and to operate our community. Although most web browsers automatically accept cookies, many browsers’ settings can be set to decline cookies or alert you when a website is attempting to place a cookie on your computer. However, many of our community features may not function properly if you disable cookies. We do not support the Do Not Track browser option. You can learn more about how we use cookies and similar technologies here.

We use cookies for the following purposes

1.4.1 Authentication – we use cookies to identify you when you visit our community. When you create a topic or post a reply as guest (not registered user) we store your name and email address in cookies. We use this information to detect current visitor content (topics, posts) and display it to you even if the content is under moderation (not approved by moderators). The name is used to display as topic/post author name. Also we store your name and email in cookies to keep filled these fields when you post a new reply or create a new topic (you don’t heave to fill these information every time you post a content). We recommend don’t use guest posting option on non-personal devices, or at least delete browser cookies when you leave it.

1.4.2 Status – we use cookies to help us to determine if you are logged into our website.

1.4.3 Security – we use cookies as an element of the security measures used to protect user accounts, including preventing fraudulent use of login credentials, and to protect our website and services generally.Cookies used by our service providers

1.4.4 Our service providers use cookies and those cookies may be stored on your computer when you visit our website.

1.4.5 We use Google Analytics to analyse the use of our website. Google Analytics gathers information about website use by means of cookies. The information gathered relating to our website is used to create reports about the use of our website. Google’s privacy policy is available at: https://www.google.com/policies/privacy/ .

1.4.6 We publish Google AdSense interest-based advertisements on our website. These are tailored by Google to reflect your interests. We publish Google AdSense advertisements on our website. To determine your interests, Google will track your behaviour on our website and on other websites across the web using cookies. This behaviour tracking allows Google to tailor the advertisements that you see on other websites to reflect your interests (but we do not publish interest-based advertisements on our website). You can view, delete or add interest categories associated with your browser by visiting: https://adssettings.google.com. You can also opt out of the AdSense partner network cookie using those settings or using the Network Advertising Initiative’s multi-cookie opt-out mechanism at: http://optout.networkadvertising.org. However, these opt-out mechanisms themselves use cookies, and if you clear the cookies from your browser your opt-out will not be maintained. To ensure that an opt-out is maintained in respect of a particular browser, you may wish to consider using the Google browser plug-ins available at: https://support.google.com/ads/answer/7395996.

1.5 Log Data

We receive information when you view content on or otherwise interact with our community, which we refer to as “Log Data,” even if you have not created an account. For example, when you visit our websites, sign into our community, interact with our email notifications, we may receive information about you. This Log Data includes information such as your IP address, browser type, operating system, the referring web page, pages visited, location, your mobile carrier, device information (including device and application IDs), search terms, and cookie information. We use Log Data to operate our services and ensure their secure, reliable, and robust performance. We use information you provide to us and data we receive, including Log Data and data from third parties, to make inferences like what topics you may be interested in and what languages you speak. This helps us better design our services for you and personalize the content we show you.

2. Information We Share and Disclose

2.1 How we share information we collect

You should be aware that any information you provide on our community – including profile information associated with the account you use to post the information – may be read, collected, and used by any member of the community who access the website. Your posts and certain profile information may remain even after you terminate your account. We urge you to consider the sensitivity of any information you input into these Services. To request removal of your information from publicly accessible websites operated by us, please contact us. In some cases, we may not be able to remove your information, in which case we will let you know if we are unable to and why.

2.2 Sharing with third parties

2.2.1 Service Providers: We share information with third parties that help us operate, provide, improve, integrate, customise, support and market our services. We work with third-party service providers to provide website and application development, hosting, maintenance, backup, storage, virtual infrastructure, payment processing, analysis and other services for us, which may require them to access or use information about you. If a service provider needs to access information about you to perform services on our behalf, they do so under close instruction from us, including policies and procedures designed to protect your information.Our administrators may choose to add new functionality or change the behaviour of the community by installing third party apps within the community. Doing so may give third-party apps access to your account and information about you like your name and email address, and any content you choose to use in connection with those apps. Third-party app policies and procedures are not controlled by us, and this privacy policy does not cover how third-party apps use your information. We encourage you to review the privacy policies of third parties before connecting to or using their applications or services to learn more about their privacy and information handling practices. If you object to information about you being shared with these third parties, please uninstall the contact us and let us know as soon as possible.

Below are the third party services we use on our community:

2.2.2 Links to Third Party Sites: Our community may include links that direct you to other websites or services whose privacy practices may differ from ours. If you submit information to any of those third party sites, your information is governed by their privacy policies, not this one. We encourage you to carefully read the privacy policy of any website you visit.

2.2.3 Social Media Widgets: The Services may include links that direct you to other websites or services whose privacy practices may differ from ours. Your use of and any information you submit to any of those third-party sites is governed by their privacy policies, not this one.

2.2.4 Third-Party Widgets: Some of our Services contain widgets and social media features, such as the Facebook “share” or Twitter “tweet” buttons. These widgets and features collect your IP address, which page you are visiting on the Services, and may set a cookie to enable the feature to function properly. Widgets and social media features are either hosted by a third party or hosted directly on our Services. Your interactions with these features are governed by the privacy policy of the company providing it.

2.3 Law, Harm, and the Public Interest

Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this Privacy Policy or controls we may otherwise offer to you, we may preserve, use, or disclose your personal data if we believe that it is reasonably necessary to comply with a law, regulation, legal process, or governmental request; to protect the safety of any person; to protect the safety or integrity of our platform, including to help prevent spam, abuse, or malicious actors on our services, or to explain why we have removed content or accounts from our services; to address fraud, security, or technical issues; or to protect our rights or property or the rights or property of those who use our services. However, nothing in this Privacy Policy is intended to limit any legal defences or objections that you may have to a third party’s, including a government’s, request to disclose your personal data.

2.4 Non-Personal Information

We share or disclose non-personal data, such as aggregated information like the community statistic (online users, visitors, current viewers of a topic, etc…), the number of people who clicked on a particular link (number of topic views) or voted on a poll in a topic (even if only one did).

3. How to access and control your information

3.1 Accessing or Rectifying Your Personal Data

You have the right to request a copy of your information, to object to our use of your information. If you have registered an account on our community, we provide you with tools and account settings to access, correct, delete, or modify the personal data you provided to us and associated with your account. You can request for downloading your account information, including your created content (posts). You also can request correction, deletion, or modification of your personal data.Your request and choices may be limited in certain cases: for example, if fulfilling your request would reveal information about another person, or if you ask to delete information which we or your administrator are permitted by law or have compelling legitimate interests to keep. Where you have asked us to share data with third parties, for example, by installing third-party apps, you will need to contact those third-party service providers directly to have your information deleted or otherwise restricted.

3.2 Deletion Your Personal Data

You can request for your account deletion. This will include personal data, profile data, created content, logs, etc… Cookies should be deleted from your side. Almost all browsers have an option to delete cookies.Keep in mind that search engines and other third parties may still retain copies of your public information, like your profile information, even after we/you have deleted the information from our community.

3.3 Restrict Processing

3.3.1 Request that we stop using your information: In some cases, you may ask us to stop accessing, storing, using and otherwise processing your information where you believe we don’t have the appropriate rights to do so. For example, if you believe a community account was created for you without your permission or you are no longer an active user, you can request that we delete your account (contact us). Where you gave us consent to use your information for a limited purpose, you can contact us to withdraw that consent, but this will not affect any processing that has already taken place at the time. You can also opt-out of our use of your information for marketing purposes by contacting us. When you make such requests, we may need time to investigate and facilitate your request. If there is delay or dispute as to whether we have the right to continue using your information, we will restrict any further use of your information until the request is honored or the dispute is resolved, provided your administrator does not object (where applicable). If you object to information about you being shared with a third-party app, please disable the app or contact your administrator to do so.

3.3.2 Opt out of communications: You may opt out of receiving email notifications related to your subscribed forums and posts or promotional communications from us by using the unsubscribe link within each email, updating your subscription settings in My Profile > Subscription page, or by contacting us as provided below to have your contact information removed from our promotional email list or registration database.

3.4 Data portability

Data portability is the ability to obtain some of your information in a format you can keep in your devices or share with other communities. Depending on the context, this applies to some of your information, but not to all of your information. Should you request it, we will provide you with an electronic file of your basic account information and the information you create on the spaces you under your sole control, like your topics (only with your posts), your replies in other topics, private messages and conversations (only with your messages), etc…

4. How we store and secure information we collect

We use data hosting service providers to host the information we collect, and we use technical measures to secure your data. While we implement safeguards designed to protect your information, no security system is impenetrable and due to the inherent nature of the Internet, we cannot guarantee that data, during transmission through the Internet or while stored on our systems or otherwise in our care, is absolutely safe from intrusion by others.

5. Children and Our Community

Our community is not directed to children, and you may not use our services if you are under the age of 13. You must also be old enough to consent to the processing of your personal data in your country (in some countries we may allow your parent or guardian to do so on your behalf).

6. Online Privacy Policy Only

This online privacy policy applies only to information collected through our website and not to information collected offline.

7. Your Consent To This Policy

By using our site, you consent to our Privacy Policy.

8. Changes To This Privacy Policy

We may update our Privacy Policy from time to time. We will notify you of any changes by posting the new Privacy Policy on this page.We will let you know via email and/or a prominent notice on our Service, prior to the change becoming effective and update the “effective date” at the top of this Privacy Policy.You are advised to review this Privacy Policy periodically for any changes. Changes to this Privacy Policy are effective when they are posted on this page.

9. Contact Us

If you have any questions about this Privacy Policy, please contact us.

A few days ago I wrote a post about Marshall McLuhan’s ideas on the phonetic alphabet and finished by making some remarks about another writer, Cormac McCarthy and his book, The Road, saying that I felt that we can use language to break outside of a straight and narrow interpretation of reality and experience; contrary perhaps to McLuhan’s belief that we are straight-jacketed by our language.

A few days ago I wrote a post about Marshall McLuhan’s ideas on the phonetic alphabet and finished by making some remarks about another writer, Cormac McCarthy and his book, The Road, saying that I felt that we can use language to break outside of a straight and narrow interpretation of reality and experience; contrary perhaps to McLuhan’s belief that we are straight-jacketed by our language.